Assault & Aggravated Assault in Boston

Assaults, both “common” and “aggravated” (In Massachusetts, common assault is an unlawful attempt or threat to cause physical harm without serious injury or a

weapon, whilst aggravated assault either involves a weapon, serious bodily injury, or intent to cause grievous bodily harm) are one of Boston’s year-to-year

crime statistics that criminologists pay attention to, as they are the most common forms of violence, and so indicative as to whether Boston society is becoming

more or less violent as a whole. They account for many more incidents than shootings or homicides and often represent the frontline reality of violence for

residents. Understanding their contours e.g., where do they happen, who is involved, how they escalate etc., is essential for any comprehensive

view of public safety in Boston.

Assaults, both “common” and “aggravated” (In Massachusetts, common assault is an unlawful attempt or threat to cause physical harm without serious injury or a

weapon, whilst aggravated assault either involves a weapon, serious bodily injury, or intent to cause grievous bodily harm) are one of Boston’s year-to-year

crime statistics that criminologists pay attention to, as they are the most common forms of violence, and so indicative as to whether Boston society is becoming

more or less violent as a whole. They account for many more incidents than shootings or homicides and often represent the frontline reality of violence for

residents. Understanding their contours e.g., where do they happen, who is involved, how they escalate etc., is essential for any comprehensive

view of public safety in Boston.

Common assault under Massachusetts Law generally refers to assaults without a weapon, or with a weapon but no intent to do serious bodily harm, usually resulting in minor injuries or threat(s). Aggravated assault (assault and battery with a dangerous weapon and/or causing serious injury) moves the scale upward, featuring weapons, severe injuries, or clear intent. In Boston, common assaults outnumber aggravated ones by magnitudes, but the latter carry disproportionate harm, trauma, and demand for law enforcement resources.

Boston Police Department crime reporting shows that neighborhoods like Dorchester, Roxbury, Mattapan, and East Boston consistently record the highest numbers of assault calls, both common and aggravated. These areas have concentrations of poverty, population density, and social stressors, which correlate with higher rates of interpersonal violence (something which can often be prevented with good de-escalation training). Year to year, the Boston Annual Crime Review notes that aggravated assaults are more volatile than common assaults, spiking during social stressors (e.g., summer months, during large public events, or when policing presence is stretched). Whilst, meanwhile, common assaults such as bar fights, domestic disputes, street-level shoving, fights, track more steadily and reflect the everyday friction of urban life: intoxication, arguments, retaliatory gestures.

Assaults connected to gang activity are more often aggravated, involving weapons or intentional harm. In Boston’s gang-affected neighborhoods, many assaults begin as common disputes e.g., verbal insults, challenges, pushes etc., and then escalate into armed violence. A typical pattern is somebody feeling disrespected, pushing back physically, and then pulling a weapon etc. Local case studies highlight this escalation: for instance, in Dorchester in late 2024, an argument over territorial control turned into a knife assault that required hospitalization, that came out after a later investigation by BPD’s gang unit. Whilst not every aggravating assault leads to shooting, they reflect the escalation potential within low-level conflict zones.

Domestic violence and intimate partner assaults also form a significant slice of common and aggravated assault calls in Boston. BPD regularly coordinates with Suffolk County’s

District Attorney’s Domestic Violence Unit to process and track these cases. Many interpersonal assaults reported to police arise within households, driven by substance abuse,

economic stress, coercive control, or relationship breakdowns. These are often common assaults (shoving, slapping, minor injury) but they can occasionally escalate to aggravated

levels when weapons and/or serious injury are involved. The overlap with assault law in Massachusetts means that prosecutors must sort intent, self-defense claims, and aggravating

factors such as prior domestic violence history or presence of minors when bringing charges.

Domestic violence and intimate partner assaults also form a significant slice of common and aggravated assault calls in Boston. BPD regularly coordinates with Suffolk County’s

District Attorney’s Domestic Violence Unit to process and track these cases. Many interpersonal assaults reported to police arise within households, driven by substance abuse,

economic stress, coercive control, or relationship breakdowns. These are often common assaults (shoving, slapping, minor injury) but they can occasionally escalate to aggravated

levels when weapons and/or serious injury are involved. The overlap with assault law in Massachusetts means that prosecutors must sort intent, self-defense claims, and aggravating

factors such as prior domestic violence history or presence of minors when bringing charges.

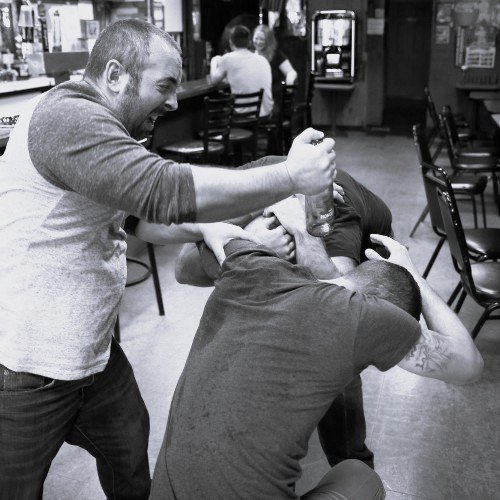

Public space assault is another frequent category: fights in bars, assaults in transit, robberies turning violent. The Boston region’s public transportation system (MBTA) and dense nightlife neighborhoods, such as Fenway, South Boston, and Allston etc., see/experience a steady stream of assault calls. Whilst many of these are categorized as “common” e.g., pushing, slapping, and bar altercations etc., some become/escalate to aggravated ones when weapons are brandished (knives, broken bottles) or when victims intervene or try to resist etc. These incidents generate high demand on emergency services, video surveillance, and public order policing. These types of assault from a personal perspective/level can be managed and mitigated through effective self-defense programs.

One challenge in interpreting Boston’s assault data is in its classification and reporting practices. Also, not all reported assaults make it into public dashboards; some are downgraded, combined, or removed. Victims may decline to cooperate, especially when the assailant is known or local. In many aggravated assault cases, victims may be taken to hospitals before police arrive, leaving initial charges uncertain. BPD’s internal review sometimes reclassifies incidents upon investigation. This means that raw counts of common and aggravated assault likely understate the true interpersonal violence burden.

From a policy perspective, prevention of assaults in Boston follows a multi-pronged strategy. On the enforcement side, precincts in high-assault areas receive overtime and visibility

policing, and BPD has invested in violent crime reduction squads that respond to aggravated violence. In parallel, Boston and partner nonprofits operate violence-interruption or

“credible messenger” programs, especially in neighborhoods with histories of retaliatory conflict. These outreach teams work to mediate disputes, connect youth to resources, and dissuade

escalation over minor shoves or taunts.

From a policy perspective, prevention of assaults in Boston follows a multi-pronged strategy. On the enforcement side, precincts in high-assault areas receive overtime and visibility

policing, and BPD has invested in violent crime reduction squads that respond to aggravated violence. In parallel, Boston and partner nonprofits operate violence-interruption or

“credible messenger” programs, especially in neighborhoods with histories of retaliatory conflict. These outreach teams work to mediate disputes, connect youth to resources, and dissuade

escalation over minor shoves or taunts.

Personal Safety Training that raises situational awareness is also key. Krav Maga Yashir Boston regularly conduct workshops on de-escalation, helping bar staff, permit holders, and citizen volunteers to recognize verbal escalation and intervene before physical assault occurs, as well as to de-escalate incidents they may find themselves involved in. In schools and youth centers, conflict resolution programs teach young people alternatives to aggression. Because many common assaults originate in momentary loss of self-control, interventions around emotional regulation, grievance communication, and peer mediation carry real potential.

Data sharing and hotspot analysis augment these efforts. BPD, in coordination with the Boston Regional Intelligence Center (BRIC), maps assault incidents at the micro-level, street segments and corners, to identify assault “hot spots/segments.” Over time, consistent high-assault micro-locations can be targeted with environmental redesign (better lighting, visibility, cameras, removal of litter) to reduce the conditions conducive to assault escalation. This aligns with the “law of crime concentration” approach, that assaults, like other crimes, cluster spatially.

Effective prosecutorial strategy also matters. Boston’s Suffolk County DA’s office uses charging differentiation: lesser assaults may enter diversion or deferred prosecution, whilst aggravated assaults are prioritized for immediate indictment, leverage in bail, and specialized prosecution units. This helps reserve court and detective resources for the most serious offenses whilst keeping lower-level intervention accessible.

Nevertheless, Boston faces ongoing challenges: balancing policing and civil liberties in high-assault neighborhoods; funding credible-messenger programs at sufficient scale; dealing with underreporting; and integrating mental health and substance-use services into the assault-prevention framework. In dense, stressed urban zones, the friction that triggers common assault is always present — but the decision to escalate is where system design, community presence, and immediate intervention make the difference between a shove and a hospital visit.

Common and aggravated assaults in Boston are not a residual or incidental problem, they form the fabric of much of the violence that residents are most likely to experience daily. Though they don’t always command headline attention like shootings or carjackings, their volume, impact, and social footprint matter deeply. Reducing them requires a layered approach, involving hotspot policing, mediation, de-escalation, social services, environmental strategy, and range of prosecutorial tools etc. When Boston’s assault baseline falls, quality-of-life rises—and so does the promise that fewer moments of conflict will turn into life-changing injury.